For some time, I’ve been meaning to write a post about ten reasons I am optimistic about our ability, as a civilization, to survive and even reverse global warming. (I don’t like to call it Climate Change because the term seems too soft, to emasculated.) There are lot of good things happening in the world right now, technologically and socially, and I list some of them below.

However, the more I thought about it, the more realized that “optimistic” just isn’t the right word. I kept remembering something that the great writer and philosopher Erich Fromm once wrote about the word “optimistic.” In his landmark book, The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness, he states:

Assume that I am planning a weekend trip to the country and it is doubtful that the weather will be fine. I may say, “I’m optimistic,” as far as the weather is concerned. But if my child is gravely sick and his life hangs in the balance, to say “I’m optimistic” would sound strange to sensitive ears, because in this context the expression sounds detached and distant. Yet I could not very well say “I am convinced my child will live,” because, under the circumstances, I have no realistic basis for being convinced.

What then could I say?

The most adequate words would perhaps be “I have faith my child will live.” But “faith,” because of its theological implications, is not a word today. Yet it is the best we have, because faith implies an extremely important element: my ardent, intense wish for my child to live, hence my doing everything possible to bring about his recovery.

Fromm, as usual, gets to the heart of the matter here (in every sense). “Optimistic” just doesn’t feel like the right word when talking about something as potentially horrendous as global warming. It would, in fact, sound fatuous, given the current looming crisis. But more importantly, the word “optimistic” would suggest a kind of arm-chair detachment from the problem, as if we aren’t, ourselves, part of the problem (and, conversely, part of the solution).

If we are to survive global warming, we must all be involved, and do everything we can to avert disaster. So, as Fromm suggests, I have chosen the word “faith” to describe how I feel about chances. It suggests hope, not mere optimism, and also a commitment to try to do something.

So, anyway, here’s the list:

1. Solar Power

This is the biggie, obviously. The history of civilization seems like a list of one “energy crisis” after another. From wood, to coal, to oil. Each time, the next energy source has been revealed as more abundant, cheaper, and more powerful. I think the trend is going continue with solar power. We live on a planet that is bathed in free, clean energy—4.2 kilowatt-hours per square meter every day. Over a year, that’s the equivalent of one barrel of oil for every square meter.

The only obstacles have been the price of and efficiency of photovoltaics and these, like every other simple engineering problem left to mankind, are being solved quickly and in a myriad of unexpected ways. This really might be the answer to all the world’s greatest problems, especially since so many of them—hunger, drought, poverty, oppression—can be rephrased as problems of energy scarcity.

The most pleasing irony about solar power is that it will be of the most use in the places that it need it the most: the equatorial regions of the earth. We may soon see a “flipping” point whereby the poorest and hottest places in the world become the richest and coolest.

2. Biochar

As with solar power, it seems incredible that something as simple as biochar might be part of the solution to the world’s greatest problems. It’s an ancient technology–the Incas used charcoal to fertilize the nutrient-poor soils of the rainforest—and it’s about as low-tech as you can get. Basically, you take any kind of leftover organic matter (grass cuttings, dead wood, weeds…whatever) and cook the hell out of it at low temperatures in a sealed oven. The result is a black, spongy, water-loving material that not only sequesters carbon for centuries but is great for crop soil.

The technical name for the low-oxygen cooking process is pyrolysis, and it does require a bit of energy. But simple, green sources of this energy—solar ovens, for example—can make biochar a win-win proposition for farmers and ranchers in even the poorest locations.

3. Biofuels

Let’s face it. We’re not going to give up the combustion engine any time soon. Even if the conversion to solar power and electric vehicles doubles in pace, there will still be millions of gas-powered engines out there, especially in shipping and industrial vehicles.

But just because a car or truck burns gas doesn’t mean it can’t be green. Biofuels are carbon-based, just like gasoline, but are produced from the fermentation of organic matter. The sources of that matter can be anything from grass-cuttings to left-over cooking grease. Biofuels are considered green because they don’t actually add any carbon to the atmosphere (the are carbon-neutral, as the saying goes). Even better, they tend to burn cleaner than petroleum-based gasoline. The real Big Kahuna of biofuel production might be fuel created from algae in on industrial scale. We might soon see the day where fuel is “farmed” across the U.S. on scales comparable to agriculture.

4. Microcredit

Again, this is an incredibly simple concept that can have fantastic global results. Microcredit is simple the idea of giving small—very small—loans to poor people who have no access to traditional credit. First conceived by the Asian banker Muhammad Yunus, the practice of lending even tiny amounts of money has proven to have a great positive on local economies in impoverished areas of Africa and India. What has this got to do with global warming? Everything. Reducing poverty is the key to avoiding climate disaster, because poor people tend to make desperate choices. (Look no further than Haiti to see how an impoverished society reacts to diminishing resources.) Poor nations are more likely to burn up oil and coal instead of building a green infrastructure, and they are more likely to go to war over basic necessities like food and water. Globalization has begun the third world’s rapid transition to modernity, but innovations like microcredit can help the remaining billion or so poor people start the climb.

5. EVs

About thirty years ago, when I was a teenager, a friend of my father’s took us for a ride in his new car. It looked like a regular car from that era, the 1970s, a boxy little sedan with wood paneled doors. But when he took us out on the road, we immediately noticed something weird about the car: it made no sound. Grinning, my father’s friend explained to us that the car ran entirely on batteries. He was, as it turned out, a pioneer in electric vehicles (EVs), doing research for the University of Florida.

At the time, I thought it was pretty neat, but hardly awe-inspiring. The oil embargoes of the mid-70s were already over, gas was getting cheap again. I was way more interested in getting myself a Corvette (which, alas, I never did). I never heard anything else about my father’s genius friend and his battery-powered car.

Now, a generation later, EVs are not only a reality, they are actually hip. I mean, Corvette-level hip. The Prius and the Leaf made EV’s mainstream, but it took Elon Musk’s Tesla Motors has liberate the EV from the sub-domain of your nerdy uncle’s garage to the parking lot of the nearest frat house. The times, my friend, they are a’ changin’. Yesterday I saw a free charging station outside of a hip condominium complex.

Cars are the second highest source of carbon-emissions in the United States, and we need to start converting more and more of our 62 million vehicles to electric.

6. Futuristic (actually, Ancient) Construction Materials

When people think of greenhouse gas, they usually think of cars and coal-fired power plants. Most people never consider that the buildings they live and work in are actually huge contributors to global warming. One study estimates that up to 39% of all greenhouse gases emitted by the U.S. come from buildings and construction.

Some of the best solutions to this problem come from new, futuring twists on ancient technologies. Specifically, wood and dirt.

Cross-Laminated-Timber (CLT) is a kind of processed lumber that is cheap, incredibly strong, and fire-resistant. Wood is nature’s best way of sequestering carbon from the atmosphere, and CLT can be derived from non-traditional sources like forests ravaged by the Mountain pine beetle. Long popular in Europe, CLT is starting to take off in the U.S., especially as local governments relax regulations on what kinds of building can be constructed from it.

Just as CLT is a new twist on wood construction, rammed earth is a new twist on the most ancient building material of all: dirt. The name says it all; rammed earth is the process of taking dirt, pouring into a wooden mold, mixing in a bit of cement or other aggregate, and then pounding the living crap out of it. Rammed earth uses about 10% as much cement as a regular cinderblock building, and it also about as cheap as…well…dirt. Rammed earth houses are naturally insulated, hypoallergenic, and (often) beautiful. Check out this great video by David Suzuki about a house constructed with rammed earth.

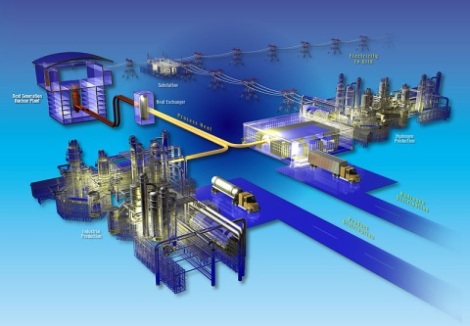

7. Next-Gen Nuclear Power

I know this will make persona non grata with a lot of my super-green friends, but I am a huge proponent of nuclear power. It’s a terrible long term solution, obviously, and it comes with a lot of risks. But even after Fukishima, nuclear remains the cleanest, safest, most reliable alternative to coal, and it’s able to handle big loads.

I visited France last summer, where half of all electric power is generated by nuclear energy, and I came to really admire the way the French have staked their future on nuclear. Unlike here, in the U.S., the French reprocess most of their spent fuel so that they only have about 10% as much waste as American plants. Yeah, I know, the waste is dangerous for thousands of years. But the carbon we are dumping in the atmosphere every day hangs around for thousands of years, too, and it’s a hell of a lot more damaging. The newest generations of nuclear power plants are not only safer (“passive safe” as they call them) but they are cheaper or more modular, making them a viable solution for even the poorest, most remote locations.

Are they still dangerous? Yes. But I’d still rather have one of the modular reactors built next to my house than a coal-fired power plant. Until solar energy scales up, nuclear power is going to play a major role.

8. This guy.

According to who you ask, the climatologist David Keith is either a hero of science or a villainous corporate stooge. He’s been one the primary researchers into the nascent field of geoengineering, which is the theoretical process of deliberated changing the earth’s climate with technology. In particular, Keith has done a great deal of research into the notion of deliberately dimming the sky with man-made particles, which would reflect solar radiation back into space in much the same way that dust from volcanic eruptions does. (The Mt. Pinatubo eruption of 1991 cooled the earth by two degrees Celsius.)

For some reason, the notion of deliberating dimming the sky sends many environmentalists into paroxysms of evangelical rage. The theory is, obviously, fraught with danger, and should only be considered as a last-ditch, absolutely bottom-of-the-drawer resort to save the planet. But, being a bit of a cynic about human behavior, I have a feeling that we’re going to need that last resort. And soon. Keith has also done a lot of groundbreaking work on carbon sequestration. His TED talk is already a classic.

9. Vertical Farming

Ever since Dr. Malthus first made his dire predictions about overpopulation in 1798, the world has been expecting a global famine. So far, we’ve managed to avoid, first through the invention of artificial fertilizers in the nineteenth century, and then with the Green Revolution of the twentieth. Now, with humanity expected to top the nine billion mark by 2050, we need to solve the food production problem yet again. The answer, I think, lies in Vertical Farming.

First popularized by ecologist Dickson Despommier, the idea of growing crops in a specialized skyscraper sounds ludicrous. But think about it; the major impediments to a successful crop are drought, bugs and poor acreage. All of these can be controlled in a closed environment—basically, a vertical greenhouse—the result being that vertical farms might actually be more efficient than a traditional farm. Water can be reclaimed and recycled endlessly, bugs never get into the system, and crops can be grown year-round, night and day. The only real limitation is power to light the crops, and this can be provided via reflected sunlight or some other form of alternative energy.

There are still lots of problems to solve, but the idea of growing organic, high-quality food inside a city is just amazing.

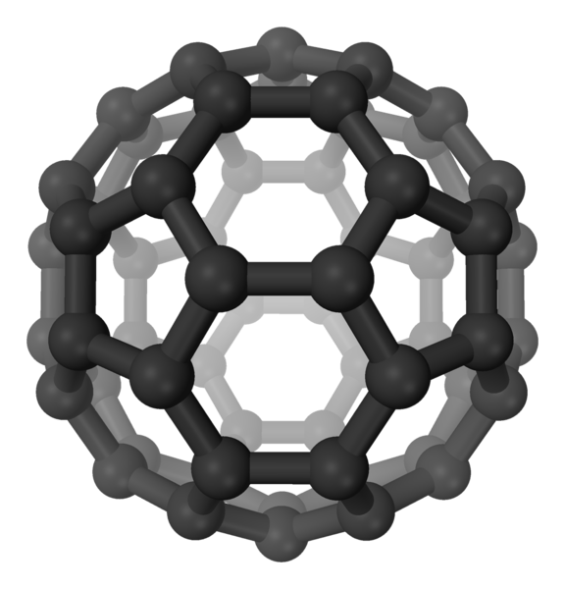

10. Carbon

It may one of the greatest ironies in human history that the very element that is most responsible for global warming—carbon—might also be the greatest boon to our civilization. For billions of years, pure carbon came in only two flavors: graphite and diamond. It wasn’t until 1985 that researchers founds a new configuration, giving it the delightful name of Buckminsterfullerene. An arrangement of 60 carbon atoms, Buckminsterfullerene is an incredibly strong molecule, and then multiple molecules are strung together, you can a tube: the now famous carbon nanotube. In the past twenty-five years, nanotubes have gone from being an laboratory exotic to a mainstay of industrial applications, although the dream of pure carbon construction has yet to be realized. I think it will be. Carbon is the sixth most common element in the earth’s crust, and, once we figure it out how to take nanotubes from the nano to the macro scale, they will revolutionize construction, engineering, medicine, and practically everything else. Thanks to our fossil fuel industry, there will be plenty of raw material in our atmosphere.